The life of a country GP before the NHS

This is the story of Lowick doctor Dr John Elliott, who lived through the enormous transformation of medical practice and welfare which happened in the first half of the 20th century before the National Health Service. Dr Elliott came to Lowick in 1899 and stayed for 57 years. When he died in Berwick Infirmary in 1956, he had served the village through two world wars and had seen great changes in the care of the sick.

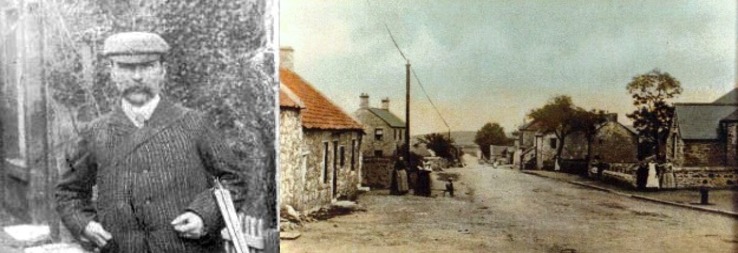

Dr John Elliott standing outside the entrance to his practice in Lowick, at the side of what is now 50 Main Street. Behind him is the passageway leading to the street. Photo: Herriott, Berwick-upon-Tweed

He was born on 21 Jan 1863 in the village of Shettleston on the outskirts of Glasgow, but he grew up in an area of Glasgow called Hutchesontown in McNeil Street, just over the Clyde from the city centre, that was subsequently incorporated into the Gorbals. His father collected payments for a life insurance firm, and by the age of 18 John was doing the same. John Elliott married for the first time in 1887 aged 24. His wife was Margaret Spence Robertson, the daughter of a tailor in the Gorbals area of Glasgow. John was widowed in 1887 when Margaret died of pneumonia and bronchitis only two months after marrying.

During the 19th century Glasgow had been transformed into a great city by mass immigration and the Industrial Revolution. It had become a major centre for heavy industry and shipbuilding and the wealth it brought in the early days resulted in the building of many elegant classically styled houses and mansions. But by the 1820s overpopulation was such a serious problem that many people were living in overcrowded and squalid conditions with poor sanitation – and many of those fine buildings were used to house a dozen or more families. By the 1840s infectious diseases like typhus and cholera were common. Disease and pollution were the status quo. Even breathing was injurious to health because of the serious smog problem, caused by the heavy industry in the area.

Air pollution had a major effect on public health in the 1800s, as this picture illlustrates. Photo: unknown source.

After moving back with his parents, John decided in 1891 to enrol at St Mungo’s college to become a doctor. He enrolled on the “Triple Qualification” courses. This qualification came about on account of the Medical Act of 1851 which required that anyone practising Medicine should have passed recognized exams and be entered on the Medical Register. While university students graduated with MD qualification, the medical colleges were allowed to provide a new qualification called the “Double” and then “Triple Qualification.” So rather than “MD”, John Elliott was listed in the Medical Register with this long list of letters:

Lic.R.Coll.Phys.Edn., Lic.Fac.Surg.Glasg., Lic.R.Coll.Surg.Edin.

Medical training was a far cry from that of today but would have equipped him well for what was possible in those days. He may have got his first taste of general medicine is as a volunteer at The Medical Missionary Society, which ran two ‘dispensaries’ in Glasgow, one of them very near to St Mungo’s college. If you earned less than 20 shillings a week you could be seen there for a charge of 1 penny.

This was a hugely valuable source of medical care when about one in five Glaswegians died without ever seeing a doctor. In 1890 it had 40,000 consultations including some home visits and these were provided by medical students as well as doctors and nurses. The ambulance service was in its infancy.

After graduation on 2nd August 1897 John Elliott lived for a short time in Gallowgate, Glasgow, before taking over the practice in Lowick, where he rented part of The Old Drapery at 50 Main Street. He was to stay on the Medical Register until his death in 1956.

Although the village was in a beautiful rural setting he would have found the living conditions familiar. There were the same dung heaps and poor sanitation in addition to a perpetual problem with the water supply. Sewerage from farm buildings was percolating through the walls onto the path and Main Street; Elliott’s own rented property was declared unfit for habitation in 1914 and narrowly escaped a closing order until the landlord made repairs.

The original Gladstone bag wasn’t originally designed for doctors but it turned out to be ideal for those visits, and being metal framed and made from sturdy leather it could open out fully without danger of tipping over. These are some of the items that Dr Elliott might have been expected to carry in the very early days; equipment at its most basic. Given a sample of the patient’s urine, he could test for diabetes using Benedict’s reagent and for kidney problems with acetic acid. He might have also carried smallpox vaccine. Smallpox vaccination had been made compulsory in 1853, and refusal could mean having to answer to the Mayor.

The Medical Officer of Health published a report in 1901 on infant mortality in this area. The cleaner air here compared to that in towns contributed to lower infant mortality, but the greatest problem, apart from sanitary conditions, was a scarcity of cows’ milk. The old system where a family might keep a cow to supply milk had all but died out. Infectious diseases such as scarlet fever, diphtheria and enteric fever spread easily in the unsanitary and crowded conditions. The most common causes of death in 1906 were TB and bronchopneumonia.

Most consultations in those days were by home visits, which of course was useful for helping to keep infectious disease out of the surgery waiting room. At no time did John Elliott own a car. He would arrive on horseback, on foot, or later on by horse and trap carrying an assortment of drugs and dressings as well as diagnostic instruments and reagents all contained in the proverbial Doctor’s Bag.

Many years later in an article written for Dr Elliott’s 93rd birthday it tells us that he did his rounds in a fierce storm one day in 1916 and is said to have walked over the frozen sea from Beal to Holy Island and that in all he managed to walk 26 miles in 12 hours “without having a bite to eat” as he attended to patients throughout his district.

Around the beginning of the century most sick people were looked after by their family or neighbours. Often someone might develop a reputation for their knowledge of traditional “home” remedies – and common sense. Few working-class people paid for their own medical treatment, with charity and the Poor Law helping the poorest. Others outside that system struggled to afford treatment. In time, municipal hospitals administered by town councils developed from Poor Law hospitals and treated the chronically sick, infirm and elderly. An increasing number of patent medicines with amazing claims were available as an alternative to calling the doctor, most proving to be of little or no use.

Despite advances in medical science, the expectation of life for the average male in 1911 was 49.

The National Insurance Act (1911)

Dr Elliott also offered dentistry – or tooth pulling. This is a (staged) picture of him demonstrating his skills.

The National Health Insurance Act (1911) meant doctors had to provide basic medical services for workers. ‘Sixpenny doctors’ were paid by the state for each patient on their panel, and as a result doctors in rural practices were a lot poorer than those in the cities. Patients still paid for home visits, with doctors charging different rates depending on the economic circumstances of families. Only 40% of the population was covered, with one panel doctor for every 1700 people insured. While being beneficial for the working man, this system largely excluded women and children.

With no chemist in the village Dr Elliott would dispense medicines himself and leave them at Pringles shop for collection where you would ‘leave a shilling in the pot’. Hospital stays had to be paid for even if you were put in one of the isolation hospitals. There were also many schemes run by donations or philanthropists, but primary healthcare was still something which most could not afford. When the doctor did visit it was treated as a special occasion in some households. Quite often there wasn’t much the doctor could do. Aspirin might have to suffice. It was not until the National Health Service was founded in 1948 that health care became free for all.

Dr Elliott had been appointed Medical Officer of Health and Vaccination Officer for Norham & Islandshire in March 1900, soon after he arrived. His catchment area included Ancroft, Fenwick, Kyloe and Holy Island. In 1904 he was elected to the Parish Council where he made some interesting contributions, such as his proposal in 1905 that every house with a private tap in the village should have a water meter. The water supply in Lowick village had always been erratic. And in 1910 he asked the Parish Council to lay out part of Lowick Common as a bowling green, for which rent would be paid if used.

Dr Elliott had connections with the military. From 1903 until 1923 he served the Admiralty as a Civil Officer, and he was on the Royal Navy “Sick Lists” or “Sick Quarters Lists” for Holy Island. This probably obliged him to be available if medical help was needed by the Royal Navy Coastguard there, and he may have attended rescued sailors or fishermen, and on occasion certified death.

A portrait of village life in Lowick in the early part of the 20th century. © Berwick Record Office.

Besides his practice, Dr Elliott was much involved in the social activities of the parish. In 1908 he presided over an evening in the Drill Hall for the Lowick & District Football league. He was donor of the Elliott Challenge Cup which he presented that evening to Fenwick Villa. He was a scoutmaster too, but ran into trouble with the council in October 1914 for encouraging scouts to skip school and help the coastguards in Bamburgh in defence duty. Later, he seems to have concentrated more on First Aid training and in 1934 he gave a talk in the Council School which was described as a most interesting and instructive lecture on Physiology of the Body as part of a series of weekly talks. And in wartime 1940 he ran courses in Holburn and Lowick that led to a certificate in First Aid.

In 1896 while Elliott was still a medical student, he had married for a second time, to Mary Hall Macrobert, and she came with him to set up his practice in Lowick in the following year. Mary’s brother Thomas was a minister in the Evangelical Union Church and one of the two ministers at the wedding ceremony. At some point between 1918 and 1928, Mary left their Lowick home. Her death certificate shows that she died in 1928 of pneumonia at her brother’s Congregational Manse in Ayrshire. They had not divorced and she still gave her address as “The Surgery” Lowick.

Dr Elliott was honoured in 1955 for his long service with a dinner and presentation. He said he hoped to keep going until he had served for 60 years, but he died in Berwick Infirmary on 5th July 1956, aged 93 years, just 3 years short. He is buried in the churchyard of St John the Baptist in Lowick.

From this aerial view of Lowick, Dr Elliott’s house can be seen with its large first floor windows. He rented the right-hand half of the house, and his patients reached the surgery and waiting room down a passage at the right.

This account is based on a talk given to Lowick Heritage Group by Eileen Langdale. Her full text provides much more detail, together with illustrations and documents. CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD IT (PDF c.3MB).